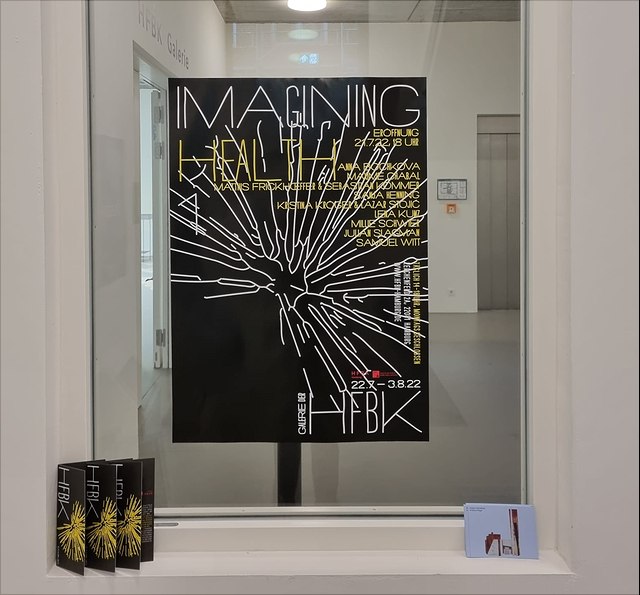

Medical Utopias in Art: Imagining Health Exhibition at HFBK

18 August 2022

Photo: UHH/Peace

Medical Utopias in Art: Imagining Health Exhibition at HFBK

How might medicine be artistically imagined? The COVID-19 pandemic has brought health to the forefront of our everyday lives, prompting reassessments of, and new imaginaries about, medicine’s future. Documenting these utopian ideals in art form brings them to life, shedding light on beneficial medical innovations that can positively impact the lives of individuals, but also reveals the negative effects of such initiatives, thus enabling an insight into how health modernisations might be best implemented in societies.

The Centre for the Study of Health, Ethics and Society at the University of Hamburg (CHES) has collaborated with the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg (HFBK, the University of Fine Arts Hamburg) to provide HFBK alumni and students the opportunity to explore the connections between scientific medical imaginaries, art, and history. Adopting a historical perspective can enable an understanding of how dreams about medicine and practices of health in the past might affect current medical imaginaries. CHES and HFBK launched a competition in February 2022 for the funding of ten artistic works, offering up to 1000 euros per project. The selected pieces are currently displayed in a collective exhibition in the gallery of HFBK.

Ahead of the exhibition launch, historians at the University of Hamburg – Dr. Kate Docking, Dr. David Peace, and Dr. Will Studdert – interviewed the artists about their work, motivated by the strong belief that interdisciplinary perspectives can spark new scholarly conversations, shift viewpoints, and greatly enrich historical writing. The discussions with the artists were fascinating, and have propelled new thoughts about how health has been imagined in the past.

While the type of art produced varies – the projects range from sculptures to self-portraits to interaction with an artificial intelligence entity – four intersecting overarching themes emerged from our conversations with the artists: the vulnerability of the body, self-care, responsibility for health, and bodily regulation, which have pertinent relevance for current and future imaginings of individual and societal health.

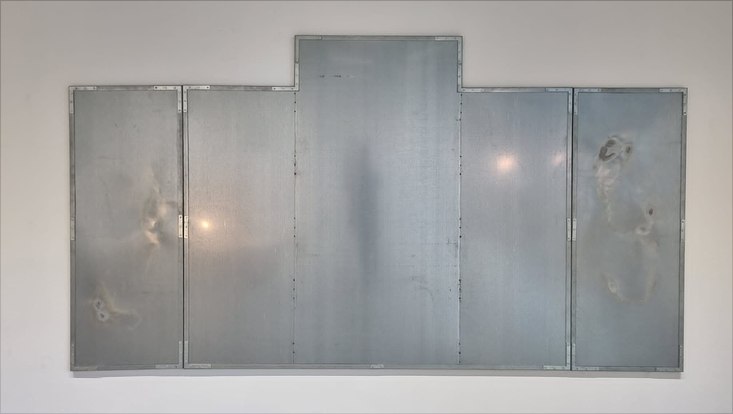

Maxime Chabal explores how representations of illness can affect viewers in his project Untitled (After Grünewald). In his work, Chabal reproduces the shape of the three central panels of the Isenheim Altarpiece, produced by Matthias Grünewald between 1512 and 1515. The painting depicts a crucifixion, which was historically shown to patients for healing purposes. Instead of focusing on the aspects related to faith, the artist was more triggered by how the singular violence of the depiction could have an assimilation effect on the spectators. By operating through the figure’s negation he decided to work with galvanised steel which is a resistant material. While steel appears strong, it can be made more fragile and sensitive to rust by heat treatment on some parts. Chabal discovered this effect by experimenting with different techniques and ways to alter the metal, contending that sometimes when materials break or react randomly, they produce a serendipitous effect. The immense size of the panels is designed to encourage viewers to come closer and engage more intimately with the vulnerability on display.

“It’s always a balance between controlled and defined operations and gestures that sometimes are unexpectedly sabotaged by random forces and events”.

Maxime Chabal, 19 July 2022

The work of Anna Bochkova also highlights the body’s vulnerability. Bochkova has produced sculptures using the materials of steel, ceramics, papier-mâché and clay, which showcase the concepts of immortality and resurrection. The fragility of the sculptures demonstrates that the body is vulnerable to manipulation for the purposes of medicine. Bochkova’s project, which is influenced by beliefs of philosophers associated with Russian Cosmism – a school of thought which propagates that immortality is not reached through dogmatic philosophical concepts but through medical innovations – raises pertinent questions concerning what medicine can do to the body, how the body changes, and bodily limits.

“I create my own dramaturgy through the objects”.

Anna Bochkova, 21 June 2022

Framing Electric Dreams, by Matthis Frickhoeffer and Sebastian Kommer, also exposes bodily vulnerability. Developed in collaboration with the AI & Art research group of Studio Kaeur, the project entails Frickhoeffer sitting in and interacting with an artificial intelligence (AI) entity, which measures his health statistics, for example, his blood pressure. This data is revealed to viewers at the exhibition on a screen. This degree of bodily exposure raises pertinent ethical issues regarding the use of such health statistics, such as who has access to them. Like Bochkova’s work, this project demonstrates that the body is vulnerable to potential ethical misuse.

Self-care

Frickhoefferand Kommer’s work also touches upon the topical theme of self-care in current medical and societal discourse, showcasing a new, futuristic way of caring for oneself. While the AI entity is not designed to provide mental health help, by having caring conversations with individuals about their daily lives – what Frickhoeffer has termed ‘nice’ interactions – it encourages them to reflect on their mental disposition in a low-pressure manner, leading to a positive mental outcome. The project thus helps to shift current negative perspectives of AI – which focus on its use in war, for example – to more positive impressions, perhaps encouraging exhibition viewers to consider the potentially beneficial impact of AI on the everyday lives of individuals while simultaneously implicitly denoting the ethical pitfalls.

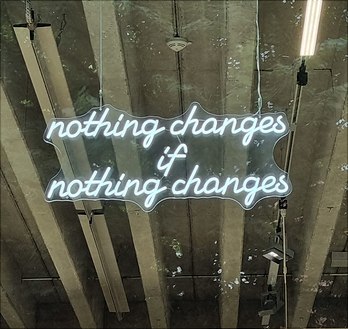

The work of Kristina Kröger and Lazar Stojić, Nothing changes if nothing changes, highlights the potential role of objects in facilitating self-care in a somewhat ironic fashion. The project is a shop-window installation with various objects relating to the concept of ‘self-care’ on display, marketed under the fake brand name ‘Level’. The objects – including a twistable stress reliever, shaped like a medical pill – relate to capitalistic versions of self-improvement, the commodification of ‘getting better’, and the notion of owning an object to make yourself feel better: ‘toxic optimism’. The fictional target group is well-off, and has ‘first-world’ problems. The store is a pop-up one, which reflects the artificial nature of the ‘self-care’ products on display. It is not initially intended to be an artwork, but becomes one on closer inspection. The project explores the tension between the notion of art as objects and objects as art. It prompts the question of whether the value of art is denigrated by having a function.

“Aesthetically pleasing is the bait because it hurts more”.

Kristina Kröger, 21 June 2022

The commercialisation of self-care is also reflected in the work of Julian Slagman, Das gute Schwimmen, which juxtaposes photographs taken by Slagman’s grandfather, Fritz Mader, during a spa break in the late 1980s with Slagman’s own images. The images printed on the towels on display critically reflect a commercial wellness and well-being aesthetic.

Allusions to self-care’s commercialisation is again present in the work of Millie Schwier, entitled Recoiling figure. The piece, which juxtaposes current aesthetics of ‘self-care’ with cultural references relating to modernist artwork and architectural language, highlights that there are more layers to ‘self-care’ than the aesthetic language cashed in on by platforms such as Instagram. Schwier’s work questions the extent to which self-care relates to the health of the self, or if it rather contributes to the individualism which propels neoliberal capitalism. Meditative objects and a collection of porcelain stones based on ‘Hagstones’, which represent human interaction with nature as a spiritual practice, are arranged to create a framework for reflection. This project explores the societal shifts between individualised and collectivised healthcare through certain moments in art history that spur an interest in the spiritual and the individual. The garden – with its connotations of growth and change – reflects these societal shifts and changes in culture.

Survival Through Self-Care, by Sanja Henning, also explores notions of individualised healthcare. Rather than pointing towards the possible future of self-care, as is evident in Frickhoefferand Kommer’s work, this project, which is a fake campaign based around the premise of ‘self-care’, highlights the current emphasis on this phenomenon by medical professionals. In so doing, it outlines some of the inadequacies in the health care system in Germany, with its focus on individual prevention and patient responsibility rather than adequate medical treatment or widely available medical appointments for people with public health insurance, a situation exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The posters produced by Henning aim to highlight that some ‘self-care’ tips can be dangerous as well as useful, for example, nutritional supplements. The colour scheme of the posters – bright – is designed to alleviate patient fear, while at the same time producing a psychological effect for the corresponding complaints. The combination of text advice and images helps to reach a broader audience, capturing those who are engaged by both visuals and written text.

Responsibility

Henning’s work also deals with the theme of responsibility, indicating in a somewhat satirical manner that patients are increasingly expected to be responsible for their own health.

The series of three nude self-portraits produced by Lena Kunz, entailed Care, places emphasis on self-responsibility. In the photo where Kunz points a finger at herself, she showcases that imagining health starts in herself. The notion of self-responsibility is abstracted through light and shadow in the self-portraits, which were taken in the film studio at HFBK with an analogue medium format camera. There is a strong metaphysical aspect to the gestures in the photographs, which display strong motions and visualise how to take self-responsibility. Kunz’s work also highlights the difficulties in being self-responsible; the image of her pointing away from herself reflects the human tendency to blame someone else for a bad experience. Indeed, Kunz contends that holding self-responsibility is a privilege, and one that must be pursued in order to communicate better with others. If everyone adopts more self-responsibility and self-reflectiveness, Kunz maintains, the world can be changed.

Regulation

Kunz’s work also alludes to the notion of bodily regulation, implicitly highlighting the societal taboos that surround nakedness. Her previous nude self-portraits showing menstruation were subjected to Instagram’s nudity rules and removed from the platform.

“It is important that we see nude bodies, but it is important how they are represented. There is a need for this, obviously people want to see a nude body, but how we do it is important – seeing a body can help people. I take the photograph, not a man – it shows how I see myself”.

Lena Kunz, 11 June 2022.

The project developed by Frickhoeffer and Kommer implicitly raises questions of how AI entities might be regulated for safe use; Frickhoeffer notes the potential problem of addiction in daily and private life. He contends that more research needs to be conducted into the long-term effects of AI on individuals before they are used in the workplace, even though theoretically, they could be used now. Bochkova’s work also brings to the fore the issue of how the quest for immortality might be ethically regulated, while Henning’s project ironically suggests how individuals might regulate their own bodies through self-care methods.

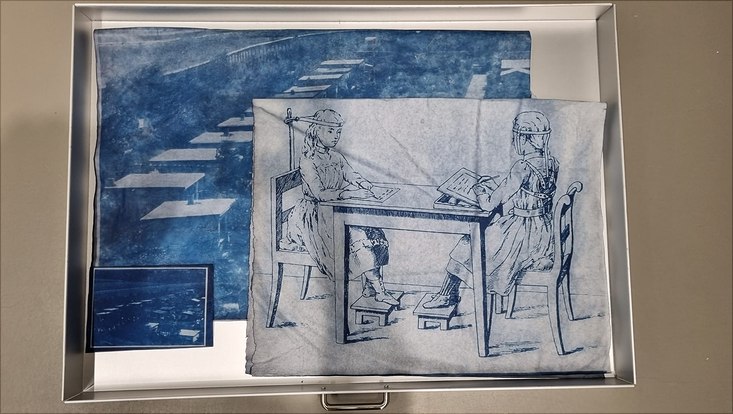

Samuel Witt’s work, In Schreber’s garden, also draws on the theme of regulation; the control of children’s bodies in the nineteenth century are juxtaposed with the contemporary regulation of Schrebergärten (allotment gardens) in Germany. His work displays ten photographs of Schrebergärten, which connote the phenomenon of health being planned and controlled on a wider level, since individuals’ gardens are often vigorously regulated. The artist therefore conceptualises Schrebergärten as a mode of biopolitical control. These photographs are set alongside blueprint images of leather belts displayed in metal drawers. The leather belts were invented by Moritz Schreber (1808-1861) and used as an instrument to control ‘badly behaved’ children, aiming to regulate their sexuality by preventing masturbation. The artist links the fear of ‘untamed sexuality’ – evident in the belt images – with the fear of the ‘untamed garden’ with its prevalence of weeds, reflected in the photographs of allotment gardens. By juxtaposing the allotment gardens with Schreber’s belts, the artist aims to demonstrate the interrelatedness between nature and culture, question the historical contingency of the fear of the untamed and ‘different’, and to uncover the extent to which somatic control, pedagogy, fetishization of nature and the solutions provided to the problem of post-industrial society are affected by restrictive ideologies today.

Other pertinent themes also link the work of the artists together. Their subjective experiences have informed the projects produced; the work of Henning has been greatly influenced by her experiences working as a physiotherapist. She has observed the increasing anxieties amongst patients about their own health, which relate to the topics depicted on the posters (for example, insomnia and depression). Bochkova’s family of doctors first exposed her to the fragility of the body, while Kunz’s training to become a life coach made her learn about self-responsibility, since this was a topic in the sessions with individuals. Doing so has spurred her own thinking on the subject, encouraging her to contend that while you need to take care of yourself, you should not damage yourself by taking responsibility. The motivation to open up discussions around contentious issues is also present in many of the works. Kunz’s work encourages individuals to reflect on their own responsibility and is also a feminist statement.

“I want people to take their power – when people see my images they take their power”.

Lena Kunz, 11 June 2022.

Henning’s project aims to open up a discussion surrounding the ambivalences of the healthcare system; her motivation was to create something important, but not in a simplistic way. The projects of Schwier, Witt, and Krögerand Lazar Stojić’s work contain inherent political criticism.

The artists provided fascinating interpretations of the theme ‘Imagining Health’, drawing upon the themes of body vulnerability, self-care, responsibility for health, and bodily regulation utilising a variety of different artistic materials and methods. We have very much enjoyed the collaboration with HFBK, and will be launching a similar competition next year.

The exhibition Imagining Health runs from 22 July to 3 August 2022, daily between 14.00 and 18.00, at the HFBK gallery (AtelierHaus Lerchenfeld), 22081 Hamburg. See also https://www.hfbk-hamburg.de/de/aktuelles/kalender/opening-imagining-health-i/.