Artistic Utopias: “Imagining Health”

8 December 2022

Photo: Tom Nestler

Image Credit: Tom Nestler

Rarely has our society contemplated the aims of medicine and health so intensively as in the last two years during the Covid-19 pandemic. Medical science and particular themes around vaccines and vaccine research have been subjected to public observation and debate. Hardly a day went by during the last two years without public scrutiny of public health measures, Covid-19 case numbers, benefits and drawbacks of different vaccines as well as the pandemic cost factor for our society, with health, being and keeping healthy extolled as a panacea.

All of these themes assumed a prominent place in our lives, therefore it might not be surprising that it also spurred the interest of artists. This dialogue has been fostered through a collaboration of the Centre for the Study of Health, Ethics and Society at the University of Hamburg (CHES) and the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg (HFBK, the University of Fine Arts Hamburg) to provide HFBK students the opportunity to explore the medical and health related topics in their art works.

Art works concerned with medical topics have existed for many years, often highlighting themes of personal illness, such as Edvard Munch’s self-portrait while infected with the Spanish Flu (1919), or displaying medical equipment, like Joseph Beuys’s Alarm I and II (1983) which comprises an arrangement of two red crucibles and a blood transfusion bag with tubes. Art works have also utilized medical images, as seen in Marilene Oliver’s Family Portraits (2001) based on MRT (magnetic resonance tomography) scans.

The collaboration between the CHES and the HfbK fostered a variety of artworks concerned with the overarching theme of “health”. The art historical approach to analyze and interpret art works corresponds, as Susan Sontag has put it in her book “Against Interpretations” (1964), to the illusion that there are actual aspects of content in an artwork.[1] This article explains and interprets the art works of the “Imaging Health” exhibition in a wider context; however, it will also bear in mind the observation made by the French artist Georges Braque (1882-1963): “There are certain secrets, certain mysteries in my work which even I don’t understand, nor do I try to do so […].”[2]

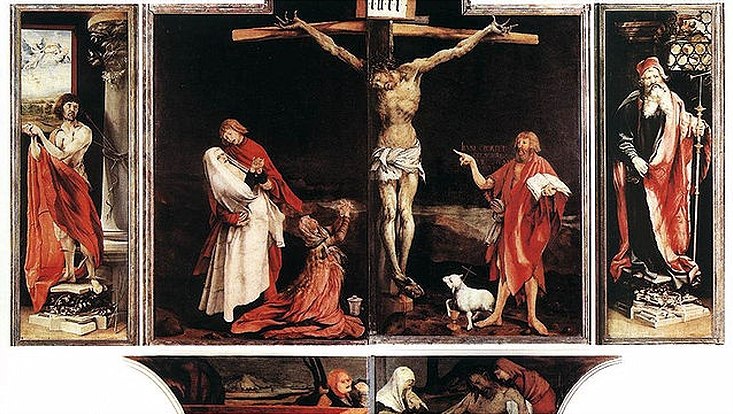

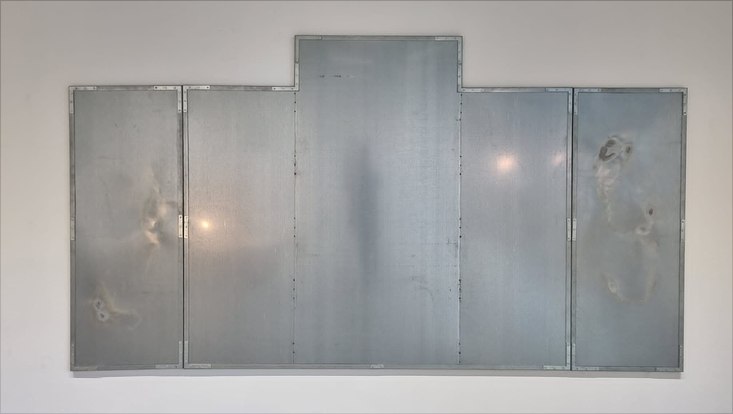

Chabal, Untitled (After Grünewald), 2022.

Maxime Chabal, who attends the class of Pia Stadtbäumer at the HfbK, exhibited a galvanized steel triptych referring to the Isenheim triptych (1512-1516) by Nikolaus von Hagenau and Matthias Grünewald. The closed Isenheim altarpiece displays the crucifixion at the center accompanied by two saints that protect and heal the sick: the left side showcases the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian regarded as a saint with a special ability to protect against the plague and on the right side Saint Anthony the Great is depicted, who was seen as a protector against infectious diseases, particularly skin diseases. Grünewald’s Crucifixion focuses on Christ’s suffering and agony while representing his body covered with plague-types sores, bruises and wounds, leaving the spectators in no doubt about his misery. Crucifixion scenes were a frequent pictorial topic during medieval times. However, Grünewald’s way of portrayal differs from that of his predecessors and contemporaries: never before were the events on Golgotha portrayed so painfully and shockingly, strongly highlighting Christ’s distress and torment. In addition, the sheer size of the triptych with a height of 269 cm and a width of 307 cm was remarkable;it was one of the largest ever created in European paintings. The altarpiece was painted for the Monastery of St. Anthony in Isenheim near Colmar where the monks treated plague sufferers. The depiction of Christ with similar symptoms was meant to emphasize that Jesus understood their pain.

Chabal’s reference to the Isenheim triptych rests on the overall form and shape of the altar piece: a large middle panel flanked by two smaller side panels. He appropriates the “three-fold” of the altar, which is usually divided into three panels that are hinged together and which can be displayed while open or shut. However, as a strong contrast to Grünewald’s Renaissance paintings, Chabal aims for a non-figurative representation. The spectator is left with a surface of galvanized steel. It is the utilization of steel and its manufacturing process that seem to make the strongest iconographic reference to the Isenheim triptych. Galvanizing refers to the process of coating the metal with zinc to achieve corrosion resistance and an uncompromised durability, where the zinc layer acts as a kind of barrier between the steel and the atmosphere. Here Chabal made the decision to weld the steel panels at a higher temperature then recommended, which is an exercise that needs to be done with caution given on one hand the toxic zinc fumes that can evaporate from the galvanized surface and on the other hand resulting in the peeling of the zinc at the intermetallic layer. On closer inspection the spectator notices the chemical injuries that the otherwise almost indestructible steel had suffered through its production process, appearing also like a reminiscence of the craquelure in Grünewald’s painting. The most severe chemical reactions and destructions of the steel are in the side panels, which display the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian and the father of all monks Saint Anthony. Chabal appropriates the shape and form of the triptych without the predella, the only reference to a sacred form given. His focus than shifts to an industrial utilized material like steel and its chemical treatment, which becomes a substitution for Christ’s crucifixion and his suffering and agony.

Lena Kunz who attends the class of Thomas Demand as well as the class of Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin at the HfbK displayed three photographic full-length nude self-portraits. In each portrait Kunz appears in a cone of light surrounded by total darkness. The photographic series depicts Kunz during the process of pointing with the right arm towards her naked body until she reaches her sternum with her hand. Kunz has referred to the series as “a visual allegory” that illustrates the starting point of health in oneself and the obligation to take care of oneself.

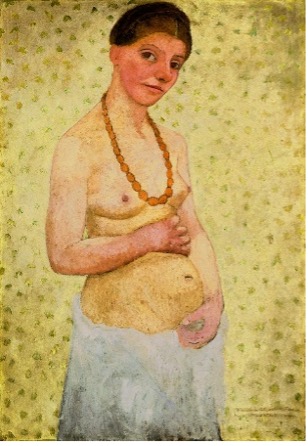

Kunz also was inspired by Expressionist artist Paula Modersohn-Becker’s (1876-1907) Self-Portrait, Age 30, 6th Wedding Day” (1906), which is seen as the first full-length nude self-portrait by a woman in Western art. Modersohn-Becker painted herself during her pregnancy with her daughter Mathilde. She died apparently of a thrombus just eighteen days after giving birth. Modersohn-Becker’s portrait was on several accounts unusual. Firstly, it represented a pregnant women nude against all social conventions of the early 20th century. Secondly, she gazes directly at the viewer, positioning herself in front of a decorative background without any staffage. Thirdly, and most importantly, as a female painter, she offers us her representation and perception of her female body, straying away from the common western tradition of the early 20th century of female nudes depicted as a pleasure for the male gaze.

Processes of female objectification and their consequences have been investigated in numerous studies, for instance the American psychologists Barbara Lee Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Roberts, who analyzed the consequences of objectifications for women’s physical and mental health in their article.[3] In a culture that sexually objectifies the female body, an occurrence that can take place, according to Fredrickson and Roberts, through gazing, comments, harassment, and violence, women will inevitably internalize a view of oneself as an object. This can result to attentive monitoring of their body and lead to mental health risks including for instance depression, eating disorders and anxiety disorders.

Nude bodies have been a major focus in Western art. Female artists have taken charge of the process of objectification by establishing the right formal and representational elements for their nude self-portraits, which is mainly interpreted as an empowerment of women. This approach also has balanced the significance of the author (who has created the representation) and the subject matter (who is being represented).

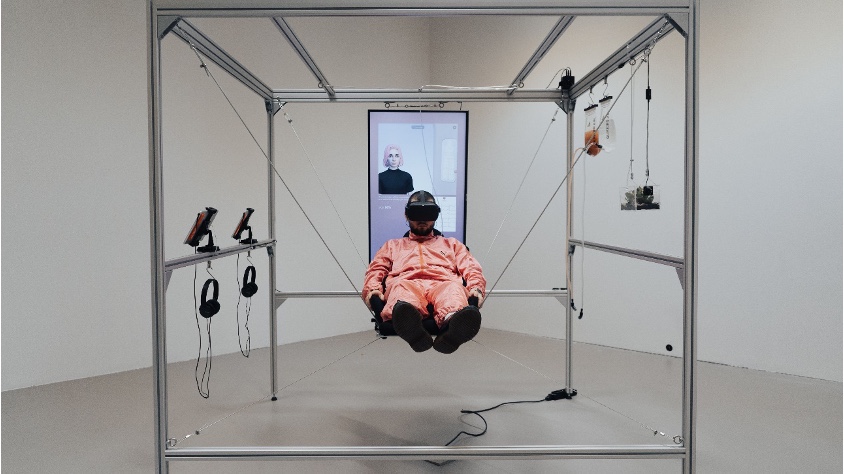

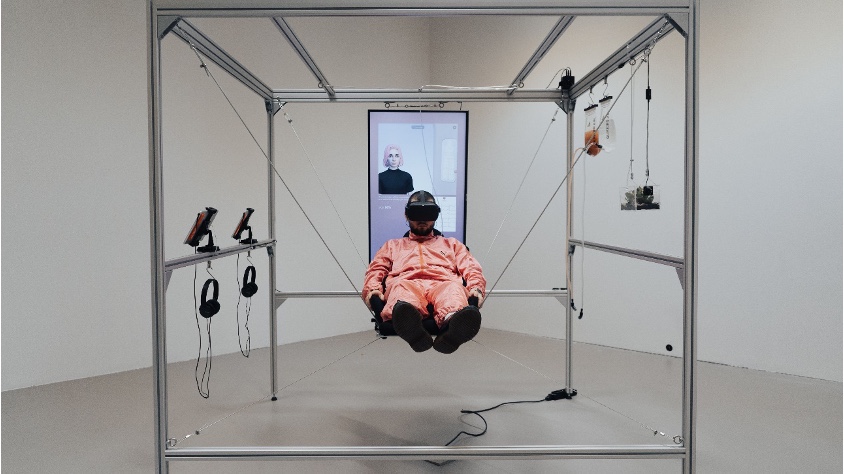

Matthias Frickhöffer/ Sebastian Kommer, Framing Electric Dreams, 2022.

Matthis Frickhöffer, who attends the time-based media class of Angela Bulloch and Sebastian Kommer, who is part of the design class of Konstantin Grcic, have opted for a performative installation. Both artists created an apparatus beneficial to physical and mental health. Embedded in a square metal scaffolding the spectator finds a seat, that has been alined to the metal bars of the construction to allow the patient, in this case Frickhöffer, to be seated, wearing virtual reality glasses and interacting with an AI-entity which analysis his vital body functions: brain activity, respiration and blood pressure. The collected data is then displayed on a screen behind Frickhöffer. In addition, two tablets are fixed on one side of the metal frame which will allow spectators to gather more information about the installation. Opposite the tablets are four trans-or infusion bags fixed to the upper metal bar, all holding certain amounts of liquid, accomplishing the overall appearance of a medical apparatus. The patient is left alone in this device, floating above the floor in an invisible bed, assessed by artificial intelligence: no medical personnel needed any longer.

Frickhöffer’s and Kommer’s work aligns well with current perceptions of health optimization as an important part of people’s daily lives. This attitude is supported by the sale of multiple devices that monitor health data: pedometers to control overall physical movement and activity levels, blood pressure monitors that can be linked to apps, heart monitoring or even electrocardiography via smart watches. People seem to have an enormous interest to take charge of and optimize their health via smart devices. In 2018 London saw its first “Health Optimisation Summit” advertising for “Biohacking, Nutrition, Longevity, Fitness, Functional and Preventative Medicine”. The message here is clear: being and staying healthy is the responsibility of every human being – therefore a machine that could assess our physical and mental needs at home without the need of any medical personnel would just come handy, particularly in times of a health crises.

Anna Bochkova, Creating and Recreating, 2022.

Anna Bochkova studies textile sculpting in the class of Pia Stadtbäumer at the HfbK. She based her mixed media installation on the philosophical movement of Russian Cosmism, which has rested on the ideas and concepts of the Russian mystic philosopher Nikolai Fyodorovich Fyodorov (1828-1903) and his circle. Fyodorov’s circle influenced their contemporaries such as Wladimir Sergejewitsch Solowjow and Lew Nikolajewitsch Tolstoi. In 1906 Fjodorov published his book “What Was Man Created For? The Philosophy of the Common Task”. He lived during times of growing militarism and civil unrest in the years before the First World War. His academic work focused on the one hand on the improvement of human life by investigating ideas about a more efficient handling of natural disasters like droughts, earthquakes or floods and on the other hand, he investigated concepts about psycho-physiological regulation of the human organisms in order to overcome death. Fjodorov’s aim was to defeat mortality and resurrect, on the ground of moral obligation, our ancestors.

Bochkova’s mixed media installation consists of materials ranging from sturdy to resistant to fragile including papier-mâché, steel, clay and ceramics. Her objects sit on top of rounded cream-colored surface structures that wind around on the grey gallery floor. There are several smaller objects in black accompanied by a white metal wired chair which appears too fragile to sit on, behind the chair one finds a white pillar, like a sculptural base. On its top rests several white wires that point in different directions and close to the gallery wall one finds a grey metal construction, seemingly appearing like a desk. Bochova’s objects seem to stand in as substitutes for Fjodorov’s concepts of immortality and resurrection.

Henning, Survival Through Self-Care, 2022.

Sanja Henning, who studies painting and drawing in the class of Jorinde Voigt at the HFBK exhibited a poster stand displaying health advice based on self-help books. Self-help books or self-improvement books certainly have a long-standing history; the earliest ones have been codes of conduct and etiquette: here one might mention the well-known “Knigge” in Germany, written by Adolph Knigge in 1788 titled “Über den Umgang mit Menschen” / “About social interactions between humans”. However, the market for self-help and improvement is a contemporary phenomenon, for instance in the United States an astonishing 18.6 million volumes were published between 2013-2019.[4] All of these publications offer some kind of promises on progress regarding health, career or relationships.

Henning’s work needs to be seen in the context of the pandemic. In the light of a global health crises caused by Covid-19, healthcare systems worldwide were placed under severe stress and came quickly to the limit of their capacities. Government public health campaigns often emphasized the responsibility of the individual during the pandemic and the commitment to follow public health advice in order to stay healthy and protect others. At the beginning of the pandemic, the German healthcare system, like many other healthcare structures around the world, was in a constant state of emergency. To relieve the strain on the health system, surgeries had to be postponed, patients had to accept waiting times, triage systems were introduced. The topics of health care and prevention came to the fore, which for many people are synonymous with the use of self-help books and alternative healing methods and advice.

Even the Federal Ministry of Health in Germany gives citizens advice on its website about “Gesundheitsförderung” (health promotion) and preventative responsibility for one’s own health by stating that: “Most diseases are not inherent but occur in the course of life. In a society of longer life, specific supportive health measurements and disease prevention at every stage in life are crucial to ensure that we grow up healthy and become older – with a high quality of life. Preventive measures are directed in particular at the health-relevant behavior of individuals, while health-promoting measures are also aimed at improving the health-relevant living conditions of society. Both approaches help the halting and reduction of chronic non-contagious diseases. [5]”

Henning’s fictional poster campaign mirrors these strategies of individual health responsibility and prevention measurements. Resembling an advertising campaign, the spectator will find appealing colors surrounded by easily understandable lettering with the promise of better health.

Julian Slagman, Das gute Schwimmen, 2022.

Julian Slagman studies at the HDK-Valand Academy of Art and Design in Gothenburg, Sweden. The idea for this display came from Slagman’s discovery of a stack of slides his grandfather took in the 1980s at a so-called “Kur”, best translated as “Health Therapy”, after being sent there by his general practitioner. The rehabilitation clinic he went to still still exists in Reinhardshausen, Bad Wildungen in Lower Saxony. At the time these stays were paid for by statutory health insurance. Slagman exhibited scanned sections of the slides his grandfather Fritz Mader took and enlarged them for display alongside his own photographic works printed on towels hanging on a towel rack. Slagman’s overarching subject matter is water, reflecting the use of water for pain relief and treatment during a “Kur”. His work can be seen as a reminder of the shift that took place in Germany from curing an illness to preventing an illness. While “die Kur” was offered to people suffering from illness and in need of rehabilitation, nowadays “spa treatments” are preferred and privately paid for, which emphasizes the idea of preventative health and self-improvement.

The German spa-industry has its origins in the “Kur”, which was prescribed by a doctor to patients, offering several weeks in a sanatorium. Historically “die Kur” is mainly associated with the treatment of tuberculosis, an infectious lung disease that spread rapidly during the 17th and 18th centuries. The best-known advocate of the “Kur” was the pastor Sebastian Kneipp (1821-1897), who apparently healed himself from tuberculosis by using natural remedies and a particular form of hydrotherapy. Kneipp’s water treading pools can often be found near spa facilities and hiking trails throughout Germany. In the absence of, for example antibiotics, a complete change in lifestyle was seen as a solution to cure patients, which then had to undergo a strict regimen under medical supervision to ensure times of rest, activities in fresh air, swimming as well as various water and temperature treatments. Patients were also offered meals to suit their needs and strengthen their immune system. All was done to assist patients in the recovery process from illness and rehabilitate them in order to become healthy again, a cause seen as worthy to be paid for by all members of the statutory health insurance to ensure “das Gemeinwohl” – “the common good”.

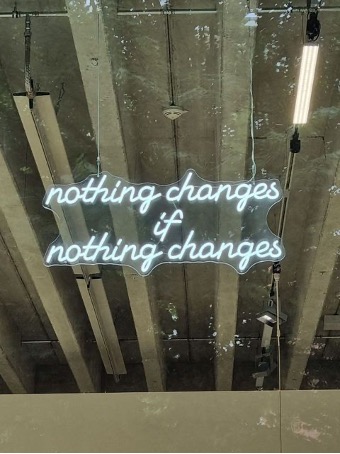

Kröger / Stojić, Nothing Changes if Nothing Changes, 2022.

Kristina Kröger and Lazar Stojić study at the sculpture department and attend the class of Martin Boyce. By approaching the HFBK gallery visitors can have a sneak peek of the exhibits through an enormous window. For this exhibition, the immediate visible display resembles the storefront of an upmarket furniture design store, with a neon sign in nice cursive handwriting stating “nothing changes if nothing changes”. The spectator is confronted with a selection of wooden furniture: two writing desks, a cabinet, a bed side table and a small shelf. On top of this furniture carefully arranged objects are displayed: LED landscape photographs in a wooden frame, a planetary daylight lamp, a sleep-well volcano device, stress relief toys, self-help books and an anti-anxiety soundbox. The shop-window installation by Kröger and Stojić offers products of their invented brand “Level” together with fictional price tags and handwritten recommendations. All of these products give the appearance of being helpful in one way or another to our psychological and emotional well-being. The installation addresses the subject of consumerism, a theme firmly established in the art world since the 1960s and probably best linked to Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). Artists began to explore consumerism in society, where the purchase of a commodity can often be an expression of class membership or self-identity and strongly relates to the happiness of the consumer. Theproducts Kröger and Stojić offer promise the consumer relief from their mental health issues.

The subject of mental health in western society has been geared towards self-optimization, self-medicalization and self-cure. The World Health Organization (WHO) released a statement in March of this year to warn about the increase in mental health conditions in relation to the pandemic. They felt the urge to advice countries to step up mental health support and services, given the multiple stress factors that have arisen form the pandemic. The WHO observed: “Loneliness, fear of infection, suffering and death for oneself and for loved ones, grief after bereavement and financial worries have also all been cited as stressors leading to anxiety and depression. Among health workers, exhaustion has been a major trigger for suicidal thinking.”[6]

With medical services strained to their limits during the pandemic, this global health crises can be seen as an accelerator in regard to mental health issues, in particular in countries with an unequal wealth distribution, as the Equality Trust in the United Kingdom noticed: “People in more equal societies are far less likely to experience mental illness.”[7] In the United States the so-called “Behavioral Health market” rocketed during the year 2021 to a value of USD 76.44 billion with a projection to grow even further. In 2020, nearly 52.9 million Americans suffered from mental health issues. [8] In countries where health care and treatment are self-funded people often favor over the counter products to improve their mental health. From anxiety relieving oil diffuser, acupressure mats, calming adult coloring books and a plethora of health supplements, the behavioral health market offers everything as long as money can buy it.

The overarching topic of this exhibition was “Imaging Health”, in which artists explored, analyzed and questioned this theme with a variety of genres ranging from installation to sculpture and photography. Their art works showcased some of the changes that strongly effect our “health”, for instance the loss of free access to rehabilitation and cure (Slagman), the focus on self-responsibility in terms of health (Kunz), the use of artificial intelligence in healthcare (Frickhöffer/Kommer) and the lure of behavioral health products (Kröger/ Stojić/ Henning). While I am sure that numerous visitors have “loved” the exhibited art works and appreciated them as food for thought, let me close this article with a quote by Hippocrates, the father of medicine: “Wherever the art of medicine is loved, there is also a love of humanity”. In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic health and humanity regardless of nationality, ethnicity, gender or socio-economic status and the right to access and receive quality healthcare should be something to aim for.

Dr. Katja Schmidt-Mai

Research Fellow

University of Hamburg

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] S. Sontag, Against Interpretation, London 2009, Penguin Modern Classics Edition.

[2] G. Braque, Illustrated Notebooks 1917-1955, Dover 1971.

[3] Barbara L. Fredrickson / Tomi-Ann Roberts, Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks, June 1997, Psychology of Women Quarterly 21(2):173-206.

[4] “The self-help industry has exploded in recent years: According to NPD Group, U.S. sales of self-help books grew annually by 11 percent from 2013 to 2019, reaching 18.6 million volumes. Meanwhile, the number of self-help titles in existence nearly tripled during that period, from 30,897 to 85,253.”

https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/self-help-books-fill-a-burgeoning-need

[5] „Die meisten Krankheiten sind nicht angeboren, sondern treten im Laufe des Lebens auf. In einer Gesellschaft des längeren Lebens sind gezielte Gesundheitsförderung und Prävention in jedem Lebensalter von entscheidender Bedeutung, damit wir gesund aufwachsen und gesund älter werden – mit einer hohen Lebensqualität. Präventive Maßnahmen richten sich insbesondere an das gesundheitsrelevante Verhalten des Einzelnen, gesundheitsfördernde Maßnahmen hingegen setzen auch an der Verbesserung der gesundheitsrelevanten Lebensbedingungen der Gesellschaft an. Beide Interventionsansätze tragen dazu bei, dass gerade chronische nichtübertragbare Erkrankungen gar nicht erst entstehen oder in ihrem Verlauf vermindert werden.“ https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/krankenversicherung-praevention.html

[7] https://equalitytrust.org.uk/mental-health

[8] https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/u-s-behavioral-health-market-105298